Killing of Peter R. de Vries highlights press freedom challenges in Netherlands

By IPI Contributor Tan Tunali

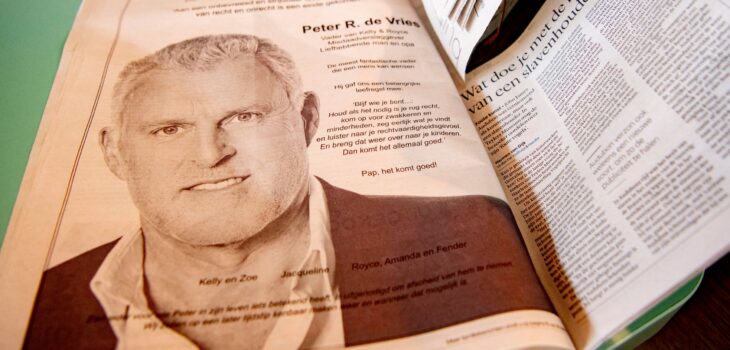

The line in front of the Royal Theatre Carré in Amsterdam was almost a kilometer long, and the waiting time was over two hours for mourners who had come to pay tribute to renowned Dutch crime reporter Peter R de Vries. The 64-year-old journalist had been shot in the evening of July 6, only moments after leaving a TV studio where he had participated in a talk show. He died in hospital nine days later.

The details behind the murder are still unknown, but the office of public prosecution has suggested a link to de Vries’ role in the so-called Marengo trial, a criminal case against leading members of a criminal organization involved in drug trafficking. De Vries had been acting as advisor to Nabil B., a former member who is testifying against Ridouan Taghi, the principal suspect in the trial.

Following the deadly attack on De Vries and threats made against the TV program, the studio moved its broadcasting to a different location outside of Amsterdam. In recent years, organized crime has been linked to threats made against other media outlets and crime reporters in the Netherlands.

In June 2018, the Amsterdam offices of leading Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf was attacked when a van repeatedly rammed the paper’s entrance before been set on fire by the driver. In the same month, the editorial offices of weekly Panorama were attacked with an anti-tank weapon. Perpetrators were convicted to prison sentences, but the exact background of the attacks remains unclear.

The killing of de Vries comes at a time when the media in the Netherlands are under increasing pressure. For the moment, the country still ranks high on international freedom of expression lists. However, the Netherlands witnessed a clear drop on the World Press Freedom Index last year.

Last year, Dutch public broadcaster NOS decided to scrub its well-known logo from satellite busses and other equipment amidst a rise in attacks on the station’s journalists reporting from anti-government demonstrations, often related to protests against the Dutch government’s Covid-19 measures. The decision came as a shock to large parts of the Dutch public.

However, many of the county’s journalists were less surprised because they had experienced the increasingly hostile environment themselves. NOS editor-in-chief Marcel Gelauff warned in a statement after the decision to forego the station logo: “Journalism is under attack of people who only want to see their own world[view], trying to impede other perspectives, hence harming press freedom.”

Increasing attacks on journalists

The global Covid-19 pandemic has also put the issue of rising violence against journalists in stark relief. Hate speech and attacks on journalists are increasing. During nationwide riots following the government’s announcement of evening curfews, stones were thrown at photographers, and camera crews were violently attacked. At a Covid-19 testing facility in the town of Urk, a NOS reporter and his bodyguard were attacked with pepper spray.

The recent outburst of physical violence towards journalists is unprecedented, but attacks have already become the norm online. Clarice Gargard, a columnist for daily NRC and founder of the feminist platform Lilith Magazine, received thousands of hate messages during the live registration of an anti-Black Pete demonstration in 2018. Gargard reported the messages to the police which eventually led to the convictions of several of the people behind the threats, who were fined or were sentenced to several hours of community service.

Several politicians in the rightwing opposition have joined the fray and publicly lashed out against the media. Leader of the far-right Freedom Party (PVV) Geert Wilders called journalists ‘riffraff’ (‘Tuig van de Richel”) in a Tweet. Thierry Baudet, leader of the far-right Forum for Democracy (FvD) repeatedly attacked the media as well, for example by repeatedly calling broadcaster NOS ‘fake news’.

In reaction to the increasing difficulties Dutch journalists are facing, the local journalist’s union NVJ, the Institute of editors-in-chief, in cooperation with the public prosecutor and the Dutch police established a joint initiative called PersVeilig (“Safe Press”) in 2019. One of the main goals of the initiative is to train and advise journalists on how to react to threats and, if necessary, to prioritize court cases against perpetrators. In the first seven months of this year, PersVeilig received 176 cases resulting in 41 reports to the police, versus 121 over the entire last year.

While the Dutch government often stresses the importance of a free press, it has been accused of playing an active role in the stifling the work of the media by preventing access to crucial state documents, something public authorities are legally bound to facilitate under the freedom of information act (Dutch: Wet Openbaarheid Bestuur, WOB). Often documents which are released arrive late and are incomplete. Sometimes they are not released at all.

Earlier this year, the government was forced to resign over a childcare subsidies scandal, in which the government withheld crucial information to press and parliament, allowing state misconduct to continue, at great human cost to the victims who in some cases lost their livelihoods.

In the cabinet’s resignation, prime-minister Mark Rutte, promised ‘a new governance culture’, and ‘more transparency’. But old habits die hard. Recently, the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (VWS) lost a court case against current affairs program Nieuwsuur. The journalists had demanded access to state documents regarding the handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. However, instead of putting the caretaker prime minister’s promise of more transparency into practice, the ministry defied the court and refused to provide the requested documents, appealing the court order instead.

Compared to their colleagues in many other countries of the world, journalists in the Netherlands are able to freely investigate and work. However, as the events of the past few years have shown, a sense of deteriorating safety for the media is a slippery slope even in a country that until recently led international press freedom rankings.

This article is part of IPI’s reporting series “Media freedom in Europe in the shadow of Covid”, which comprises news and analysis from IPI’s network of correspondents throughout the EU. Articles do not necessarily reflect the views of IPI or MFRR. This reporting series is supported by funding from the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom and by the European Commission (DG Connect) as part of the Media Freedom Rapid Response, a Europe-wide mechanism which tracks, monitors and responds to violations of press and media freedom in EU Member States and Candidate Countries.